Your cell phone helps you keep in touch with friends and families, but it also makes it easier for the feds to track your location.

Your Web searches about sensitive medical information might seem secret, known only to you and search engines like Google. But by logging your online activities, these companies are creating a honeypot of personal information, potentially available to any party wielding a subpoena.

And the next time you try to board a plane, watch out—you might be turned away after being mistakenly placed on a government watch list based on erroneous data.

Technology isn't the real problem, though; rather, the law has yet to catch up to our evolving expectations of and need for privacy. In fact, new government initiatives and laws have severely undermined our rights in recent years.

Privacy rights are enshrined in our Constitution for a reason — a thriving democracy requires respect for individuals' autonomy as well as anonymous speech and association. These rights must be balanced against legitimate concerns like law enforcement, but checks must be put in place to prevent abuse of government powers.

EFF fights in the courts and Congress to extend your privacy rights into the digital world, and supports the development of privacy-protecting technologies. Donate to EFF to help support our efforts.

Government search and surveillance powers

Rather than limit how increasingly intrusive surveillance technologies can be deployed, the government has consistently extended its power to spy on you and to force others to turn over personal information. When Congress enacted the USA PATRIOT Act, it dramatically expanded search and surveillance powers and eliminated checks and balances that previously gave courts the opportunity to ensure that those powers were not abused. EFF has fought for PATRIOT reform and has helped the ACLU and an unnamed ISP challenge the constitutionality of National Security Letters, a key power under PATRIOT.

- USA PATRIOT Act

- CALEA

- USA v. PenRegister (Cell phone tracking)

- More Surveillance Resources

- The Real ID Act

EFF filed a class-action lawsuit against AT&T on January 31, 2006, accusing the telecom giant of violating the law and the privacy of its customers by collaborating with the National Security Agency (NSA) in its massive and illegal program to wiretap and data-mine Americans' communications. The lawsuit alleges that AT&T not only helped the NSA listen in on millions of ordinary Americans' Internet and telephone communications, but also provided access to its databases containing records of most or all communications.

EFF filed a class-action lawsuit against AT&T on January 31, 2006, accusing the telecom giant of violating the law and the privacy of its customers by collaborating with the National Security Agency (NSA) in its massive and illegal program to wiretap and data-mine Americans' communications. The lawsuit alleges that AT&T not only helped the NSA listen in on millions of ordinary Americans' Internet and telephone communications, but also provided access to its databases containing records of most or all communications.

Data Mining and Dataveillance

The government isn't content to exploit personal data only when someone's suspected of a crime. Instead, it wants to analyze the details of innocent Americans' lives, looking for potential threats. What if the government's notoriously unreliable databases have inaccurate information about you? Setting the record straight will be as easy as changing your credit rating — that is, nearly impossible. And once it's collected, there may be little stopping use of the data for purposes unrelated to finding criminals.

The proposed Total Information Awareness (TIA) was one of the first widely-publicized, large scale data mining programs, but the government's initiatives have since taken many other dangerous forms. For instance, though the Transportation Security Authority (TSA) promised not to do so, it collected millions of personal records to test its Secure Flight passenger screening program. TSA has since grounded the program, at least for now.

Data collection and retention

Search engines, email providers, and other Internet companies maintain increasingly vast databases that reach into the most intimate details of your life – who you communicate with, what you read, what you buy. Unfortunately, information stored with a third-party is given much weaker legal protection than that on your own computer. By tapping into these databases, the government can effectively use private companies to do its dirty work. Any litigant might also gain access using a subpoena. These common practices demand more substantive legal and technical limits.

Anonymity Online

Since the times of the Federalist Papers, anonymity has supported critical social and political discourse. Though your email address or screenname might seem to hide your identity, individuals can too easily abuse the legal system to violate your rights. Say you want to blow the whistle on some corporate malfeasance, so you post an anonymous message online. Without your knowledge, the company's CEO can unmask your identity through a frivolous lawsuit and a subpoena to your online service provider. EFF has protected many "John Does" against these types of suits. EFF also supports the development of privacy-protecting technologies.

Privacy-intrusive technologies

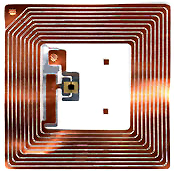

Before embracing new technologies, we must consider their privacy implications carefully. For instance, libraries, schools, the government, and private sector businesses are adopting radio frequency identification tags, or RFIDs — a technology that can be used to pinpoint the physical location of whatever item the tags are embedded in. While RFIDs are a convenient way to track inventory in a warehouse, they are also a convenient way to do something far less benign: track people and their activities through their belongings. EFF is working to ensure that use of this technology doesn't come at the expense of privacy and freedom.

Before embracing new technologies, we must consider their privacy implications carefully. For instance, libraries, schools, the government, and private sector businesses are adopting radio frequency identification tags, or RFIDs — a technology that can be used to pinpoint the physical location of whatever item the tags are embedded in. While RFIDs are a convenient way to track inventory in a warehouse, they are also a convenient way to do something far less benign: track people and their activities through their belongings. EFF is working to ensure that use of this technology doesn't come at the expense of privacy and freedom.